In an era defined by rapid change and unprecedented complexity, professionals across industries face challenges that defy simple solutions. Multi-field problem mapping emerges as a transformative approach to navigate intricate issues by drawing insights from diverse disciplines and perspectives.

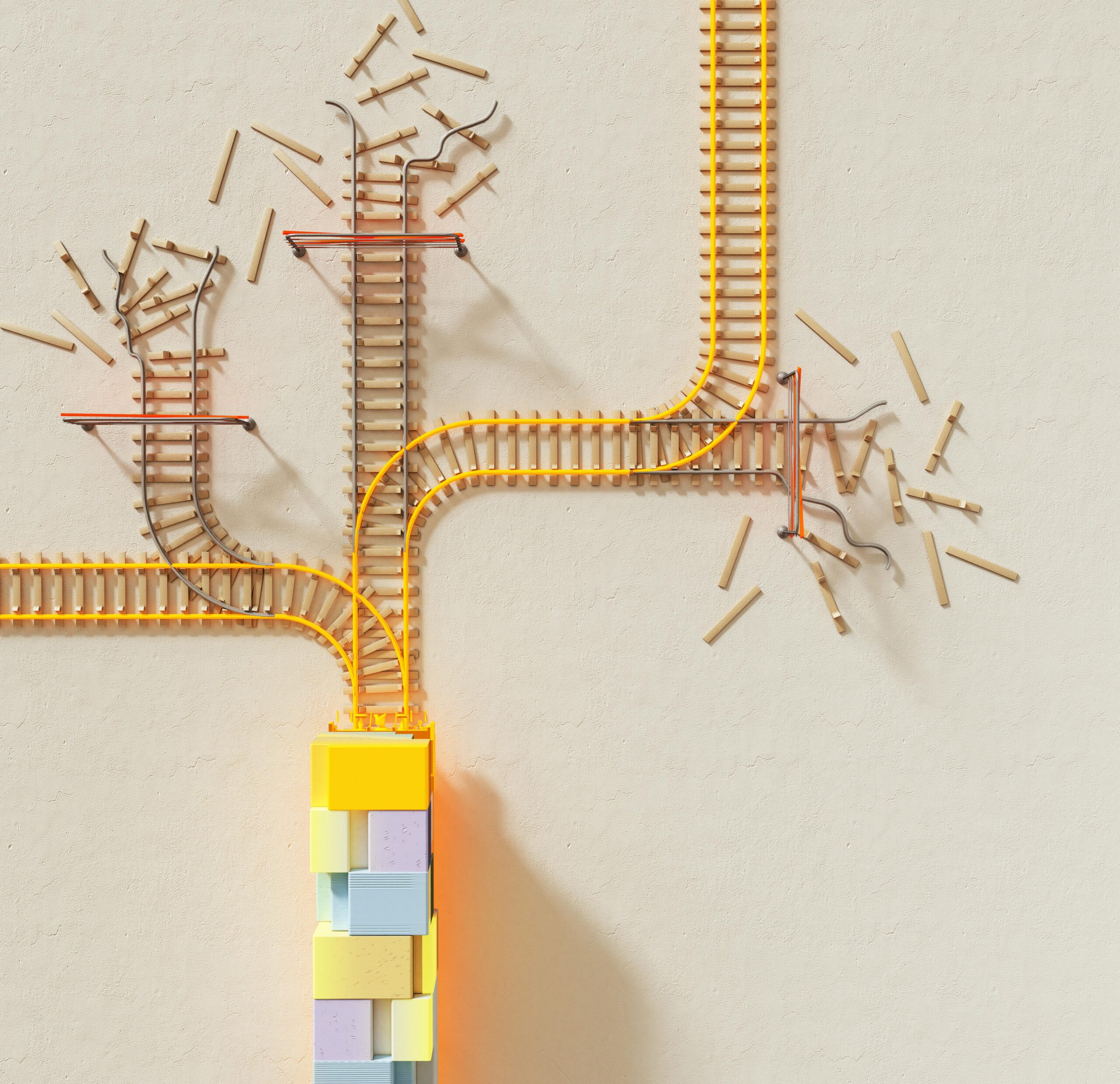

This methodology transcends traditional linear thinking, offering a structured framework to dissect complex problems, identify hidden connections, and generate innovative solutions. By integrating knowledge from multiple domains, decision-makers can unlock creative pathways that remain invisible through conventional analysis.

🧩 Understanding the Foundation of Multi-Field Problem Mapping

Multi-field problem mapping represents a systematic approach to analyzing challenges through multiple lenses simultaneously. Rather than viewing problems through a single disciplinary framework, this technique encourages practitioners to examine issues from psychological, technological, economic, social, and environmental perspectives concurrently.

The core principle revolves around recognizing that most real-world challenges are inherently interdisciplinary. A business challenge isn’t purely economic—it involves human behavior, technological constraints, market dynamics, and organizational culture. By mapping these interconnected dimensions, we create a comprehensive understanding that reveals leverage points for intervention.

This approach draws inspiration from systems thinking, design thinking, and complexity science. It acknowledges that problems exist within ecosystems where variables interact in non-linear ways, producing emergent behaviors that cannot be predicted by analyzing components in isolation.

The Architecture of Effective Problem Mapping 🗺️

Constructing a multi-field problem map begins with defining the core challenge clearly and specifically. Vague problem statements produce scattered maps, while precise definitions enable focused exploration across relevant domains.

Identifying Relevant Fields and Disciplines

The selection of fields to incorporate depends on the nature of the problem. A healthcare challenge might integrate medicine, behavioral psychology, data science, economics, and policy analysis. A sustainability issue could combine environmental science, engineering, sociology, business strategy, and political science.

Effective practitioners develop the skill to recognize which disciplines offer valuable perspectives for specific challenges. This requires broad knowledge and intellectual curiosity—the willingness to explore unfamiliar territories and engage with experts from diverse backgrounds.

Mapping Interconnections and Dependencies

Once relevant fields are identified, the next step involves charting relationships between different aspects of the problem. Visual mapping tools become invaluable here, allowing teams to document causal chains, feedback loops, constraints, and opportunities.

These maps reveal patterns that might otherwise remain hidden. A marketing problem might actually be rooted in product design issues. An operational efficiency challenge could stem from organizational culture dynamics. Multi-field mapping exposes these underlying connections.

🔍 Practical Techniques for Implementation

Implementing multi-field problem mapping requires both structured frameworks and creative flexibility. Successful practitioners balance methodical analysis with openness to unexpected insights.

Stakeholder Perspective Integration

Every problem affects multiple stakeholders, each experiencing it differently. Mapping should incorporate diverse viewpoints—customers, employees, suppliers, community members, regulators, and shareholders. These perspectives often represent different disciplinary lenses naturally.

Engaging stakeholders directly through interviews, surveys, and workshops enriches the mapping process. Their lived experiences provide data that purely theoretical analysis cannot capture. This human-centered approach ensures solutions address real needs rather than assumed problems.

Cross-Domain Pattern Recognition

Experienced problem mappers develop pattern recognition abilities that transcend individual domains. They notice when a challenge in one industry resembles a solved problem in another field. This analogical thinking enables knowledge transfer across seemingly unrelated areas.

For example, traffic flow optimization techniques from transportation engineering have been successfully applied to data packet routing in computer networks. Immune system responses inform cybersecurity strategies. Ecological succession models illuminate organizational change management.

Leveraging Technology for Enhanced Mapping 💻

Digital tools have dramatically expanded the possibilities for multi-field problem mapping. Software platforms enable collaborative mapping, dynamic visualization, and data-driven analysis at scales impossible with traditional methods.

Mind mapping applications allow teams to create interconnected diagrams showing relationships between problem elements. System dynamics software models feedback loops and simulates how interventions might affect complex systems over time. Data visualization tools transform abstract relationships into intuitive graphics.

Artificial intelligence increasingly supports problem mapping by identifying patterns in large datasets, suggesting connections between variables, and recommending relevant research from diverse disciplines. Machine learning algorithms can analyze how similar problems were solved in other contexts, accelerating the solution discovery process.

🎯 From Mapping to Action: Generating Solutions

The ultimate purpose of multi-field problem mapping is to enable better solutions. The mapping process itself often reveals intervention opportunities that weren’t initially apparent.

Identifying Leverage Points

Complex systems contain leverage points—places where small interventions produce disproportionately large effects. Multi-field mapping helps identify these high-impact opportunities by revealing the system’s structure and dynamics.

Leverage points often exist at the boundaries between disciplines or stakeholder groups. A communication breakdown between engineering and marketing teams might be the root cause of product failures. A policy misalignment between regulatory requirements and operational realities might create unnecessary friction.

Designing Integrated Interventions

Solutions derived from multi-field mapping tend to be more comprehensive and sustainable because they address multiple dimensions simultaneously. Rather than fixing symptoms, they target underlying structural issues.

An integrated solution to urban poverty might combine job training programs, affordable housing development, public transportation improvements, healthcare access, and community building initiatives. Each component reinforces the others, creating synergistic effects that isolated interventions cannot achieve.

Real-World Applications Across Industries 🌍

Multi-field problem mapping has proven valuable across remarkably diverse contexts, demonstrating its versatility and effectiveness.

Healthcare Innovation

Healthcare organizations use multi-field mapping to address challenges ranging from patient experience to operational efficiency. By integrating medical expertise, human factors design, data analytics, behavioral psychology, and systems engineering, hospitals develop solutions that improve outcomes while reducing costs.

One hospital reduced emergency department wait times by mapping the problem across clinical protocols, patient psychology, staff workflow, physical space design, and technology systems. The resulting interventions addressed bottlenecks at multiple points simultaneously, achieving improvements that previous single-focus efforts had missed.

Business Strategy Development

Companies employ multi-field mapping to navigate strategic challenges in rapidly changing markets. By examining competitive dynamics, technological trends, consumer behavior shifts, regulatory changes, and macroeconomic factors together, strategists identify opportunities and threats earlier than competitors.

A retail company facing disruption from e-commerce used multi-field mapping to reimagine its value proposition. The process revealed opportunities at the intersection of physical experience design, digital convenience, community building, and sustainability—leading to a hybrid model that leveraged strengths from multiple retail paradigms.

Environmental Sustainability

Sustainability challenges are inherently multi-disciplinary, making them ideal candidates for this approach. Climate adaptation strategies require integrating climate science, engineering, economics, social dynamics, political feasibility, and ecological principles.

A coastal community developed resilience plans by mapping flood risks across infrastructure vulnerability, ecosystem services, economic impacts, social equity considerations, and emergency response capabilities. The resulting strategy addressed physical, social, and economic dimensions simultaneously.

🚀 Building Multi-Field Mapping Capabilities

Developing proficiency in multi-field problem mapping requires deliberate practice and organizational support. Individual practitioners and teams can cultivate these capabilities through structured learning and experiential application.

Cultivating Intellectual Breadth

Effective problem mappers possess T-shaped knowledge profiles—deep expertise in at least one domain combined with broad familiarity across multiple fields. Building this breadth requires curiosity-driven learning beyond one’s primary discipline.

Reading widely, attending interdisciplinary conferences, taking courses in unfamiliar subjects, and engaging in conversations with diverse professionals all expand the mental models available for problem mapping. This intellectual diversity becomes the raw material for creative synthesis.

Developing Collaborative Skills

Multi-field problem mapping often functions best as a team activity, bringing together people with complementary expertise. This requires collaboration skills that bridge disciplinary cultures, communication styles, and problem-solving approaches.

Successful collaborative mapping involves establishing shared vocabulary, respecting different knowledge domains, managing creative tension productively, and synthesizing diverse inputs into coherent frameworks. Teams that master these dynamics generate richer maps and more innovative solutions.

Overcoming Common Obstacles and Pitfalls ⚠️

While powerful, multi-field problem mapping presents challenges that practitioners must navigate skillfully to realize its full potential.

Analysis Paralysis

The comprehensive nature of multi-field mapping can lead to overwhelming complexity if not managed carefully. Teams may continue expanding their maps indefinitely, incorporating ever more variables and perspectives without converging on actionable insights.

Setting clear boundaries and timelines helps prevent this trap. Deciding which fields are most relevant, determining appropriate scope, and establishing milestones for moving from analysis to solution design maintains productive momentum.

Disciplinary Silos and Resistance

Organizations structured around traditional disciplines may resist multi-field approaches. Experts sometimes feel threatened when their specialized knowledge is combined with insights from other domains, fearing dilution of their expertise.

Addressing this resistance requires demonstrating value through small wins, emphasizing how integration enhances rather than diminishes specialized knowledge, and creating structures that reward collaboration across boundaries.

🔮 The Future of Problem-Solving

As global challenges grow more complex and interconnected, multi-field problem mapping will become increasingly essential. Climate change, technological disruption, social inequality, and healthcare transformation all demand approaches that transcend traditional disciplinary boundaries.

Emerging technologies will enhance mapping capabilities significantly. Virtual reality might enable immersive problem exploration, allowing teams to navigate complex systems visually and intuitively. Advanced AI could suggest non-obvious connections between variables drawn from vast knowledge repositories spanning multiple disciplines.

Educational systems are beginning to recognize the need for interdisciplinary problem-solving skills. Universities are creating programs that deliberately integrate multiple fields, preparing graduates to tackle complex challenges through synthetic thinking rather than narrow specialization.

🎓 Mastering the Art of Synthesis

Ultimately, multi-field problem mapping represents more than a technique—it embodies a mindset shift toward integration, synthesis, and holistic understanding. This approach recognizes that the most significant challenges cannot be adequately understood or addressed through single-lens analysis.

The practitioners who master this approach develop a unique ability to see patterns across domains, translate concepts between disciplines, and synthesize diverse knowledge into coherent frameworks. They become valuable assets in organizations and communities facing complex challenges.

This capability isn’t built overnight. It requires sustained commitment to learning, experimentation with different mapping approaches, reflection on what works in various contexts, and continuous refinement of both analytical and creative skills.

Taking Your First Steps Forward 🌟

Beginning your multi-field problem mapping journey doesn’t require waiting for perfect conditions or comprehensive expertise. Start with a challenge you currently face, identify three different disciplinary perspectives that might offer insights, and create a simple map showing connections between them.

Engage colleagues from different backgrounds in conversation about the problem. Ask how they would approach it from their perspective. Look for patterns, contradictions, and complementary insights. Document what you discover and how your understanding evolves.

As you develop comfort with basic mapping, gradually increase complexity. Incorporate additional fields, use more sophisticated visualization tools, and tackle more challenging problems. Each iteration builds your capability and confidence.

The world needs people who can navigate complexity, bridge disciplines, and generate innovative solutions to multifaceted challenges. Multi-field problem mapping provides a structured yet flexible approach to develop these critical capabilities. By embracing this methodology, you position yourself to unlock insights that remain hidden to those confined by single-discipline thinking, ultimately driving innovation and impact across whatever domains you choose to engage.

Toni Santos is a cross-disciplinary researcher and knowledge systems analyst specializing in the integration of botanical archives, interdisciplinary research networks, and the preservation of ecological and cultural knowledge through holistic academic frameworks. Through a collaborative and systems-focused lens, Toni investigates how humanity has encoded, transmitted, and safeguarded botanical wisdom across disciplines, borders, and generations. His work is grounded in a fascination with plants not only as lifeforms, but as nodes of interconnected knowledge. From endangered ethnobotanical archives to cross-cultural datasets and collaborative research frameworks, Toni uncovers the structural and systemic tools through which cultures preserved their relationship with the botanical knowledge commons. With a background in information architecture and global research methodologies, Toni blends systems analysis with archival scholarship to reveal how botanical knowledge was used to shape interdisciplinary dialogue, preserve collective memory, and sustain holistic academic ecosystems. As the creative mind behind draxiny.com, Toni curates integrated knowledge systems, cross-field botanical studies, and collaborative interpretations that revive the deep structural ties between research, preservation, and global academic collaboration. His work is a tribute to: The endangered wisdom of Cross-Field Botanical Knowledge Systems The collaborative networks of Global Research and Academic Partnerships The integrated structure of Holistic Academic Frameworks The enduring mission of Knowledge Preservation and Digital Archives Whether you're an interdisciplinary scholar, global research collaborator, or dedicated steward of endangered knowledge systems, Toni invites you to explore the networked roots of botanical wisdom — one archive, one collaboration, one preserved insight at a time.